Lindbergh: U.S. Air Mail Service Pioneer

Air Mail Service pilots are the unsung heroes of early aviation. In their frail Curtiss Jennies and postwar de Havillands, they battled wind, snow, and sleet to pioneer round-the-clock airmail service along the world's longest air route, the U.S. transcontinental.

|

Certificate of the Oath of Mail Messengers

Download Charles Lindbergh's Certificate of the Oath of Mail Messengers document dated April 28, 1926. The file is in a PDF file format:

Charles Lindbergh & Airmail

Charles Lindbergh dropped out of engineering school at the University of Wisconsin to learn how to fly. Lindbergh applied for an aviation program in 1922 at the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation and began flight training. The next two summers he worked as a barnstormer—traveling around the western states, acting as a wingwalker and parachutist, and later sky diving. Flyers billed him as "Daredevil Lindbergh" and "Lucky Lindy." The following year, as a competent pilot, Lindbergh enlisted in the Army where they were accepting flying cadets. This time, he was shocked to learn that he had committed himself to more than flying. He was expected to attend ground school, and for the first time in his life, his passion for flying had to be tempered with real and serious study. Failing any test would result in being "washed out." But Lindbergh proved himself; by graduation in March of 1925, of the 104 cadets that had begun the program, all but eighteen had been washed out, and Lindbergh had achieved the highest ranking among his graduating class.

|

Lindbergh achieved ninety-nine percent airmail delivery efficiency even without proper equipment and landing facilities. While flying mail from Chicago to St Louis, Lindbergh decided to compete for the $25,000 prize for the first non-stop flight from New York to Paris. Although he was not the only pilot considering the feat, Lindbergh had many things going for him—an indomitable spirit and positive attitude as well as youth, energy, and a natural desire to rise to the challenge of a nonstop transcontinental flight. However, he was entering a race against time and every other enterprising pilot, and he had to be prepared. He obtained funding for a plane, and for months, between work on the small monoplane that was to become the Spirit of St. Louis, he studied charts, weather, flight plans, and memorized any piece of information that could aid him in his trip. When it came time to depart, he decided against a radio and even ripped out pages of his notebook, giving him additional weight for fuel.

It is thought that Lindbergh carried 5 covers only on this flight, although it is also believed that he was offered $1000 to carry a small package of mail, which he turned down because of his concern over weight. (Two of the five known Trans Atlantic covers have come on the market).

|

After his historic flight, Lindbergh was offered the post as Technical Advisor to the President of Pan American, to pioneer routes around the Caribbean. On 3 December he 1928 flew from Washington to Mexico City, in the record time of 27hrs 15mins. While on this Caribbean trip, Basil Rowe, a friend and fellow pilot, asked him to carry some sacks of mail and this was the only time 'Spirit of St Louis' actually carried mail. One sack was carried from Santo Domingo and two from Port-au-Prince: both to Havana. On its return to the U.S., 'Spirit of St Louis' was retired and to the Smithsonian.

The fledgling commercial air carriers were eager to have Charles Lindbergh work for them, and he joined Transcontinental Air Transport Company (TAT) for $10,000 a year and stock in 1929. On July 7th in 1929, TAT inaugurated coast-to-coast air and rail service on the route laid out by Col. Charles Lindbergh from New York to Los Angeles (Glendale) via Columbus, Ohio; Indianapolis, Indiana; St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri; Wichita, Kansas; Waynoka, Oklahoma; Clovis and Albuquerque, New Mexico; and Winslow and Kingman, Arizona. Between 1929 and 1939 the coast-to-coast route from New York to Los Angles was inaugurated and became affectionately known as 'The Lindbergh Line'.

On 10 March 1929, Lindbergh flew the inaugural flight from Brownsville, Texas to Mexico City via Tampico, in a Ford tri-motor aircraft. However numerous bags of mail went missing for one month, and consequently this became known in the philatelic world as the Lost Mail Flight.

Airmail Overview

|

With a large number of war-surplus aircraft in hand, the Post Office almost immediately set its sights on a far more ambitious goal, which was transcontinental air service. It opened the first segment, between Chicago and Cleveland, on May 15, 1919, and completed the service on Sept. 8, 1920, when the most difficult part of the route, the Rocky Mountains, was spanned. Airplanes still could not fly at night when the service first began, so the mail was handed off to trains at the end of each day. Nonetheless, by using airplanes the Post Office was able to shave 22 hours off coast-to- coast mail deliveries.

|

|

Beacons

In 1921, the Army deployed rotating beacons in a line between Columbus and Dayton, Ohio, a distance of about 80 miles. The beacons, visible to pilots at 10-second intervals, made it possible to fly the route at night.

The Post Office took over the operation of the guidance system the following year, and by the end of 1923 constructed similar beacons between Chicago and Cheyenne, WY, a line later extended coast-to-coast at a cost of $550,000. Mail then could be delivered across the continent in as little as 29 hours eastbound and 34 hours westbound (prevailing winds from west to east accounted for the difference), which was two to three days less than it took by train.

The Contract Air Mail Act of 1925 - Kelly Air Mail Act

By the mid 1920s, the Post Office mail fleet was flying 2.5 million miles and delivering 14 million letters annually. However, the government had no intention of continuing airmail service on its own. Traditionally, the Post Office had used private companies for the transportation of mail. So once the feasibility of airmail was firmly established, and airline facilities were in place, the government moved to transfer airmail service to the private sector by way of competitive bids. The legislative vehicle for the move was the 1925 Contract Air Mail Act, commonly referred to as the Kelly Act after its chief sponsor, Rep. Clyde Kelly of Pennsylvania. It was the first major legislative step toward the creation of a private U.S. airline industry. Winners of the initial five contracts were National Air Transport (owned by the Curtiss Aeroplane Co.), Varney Air Lines, Western Air Express, Colonial Air Transport, and Robertson Aircraft Corporation. National and Varney would later become important parts of United Airlines (originally a joint venture of the Boeing Airplane Company and Pratt & Whitney). Western would merge with Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT), another Curtiss subsidiary, to form Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA). Robertson would become part of the Universal Aviation Corportation, which in turn would merge with Colonial, Southern Air Transport and others to form American Airways, predecessor of American Airlines. Juan Trippe, one of the original partners in Colonial, would later pioneer international air travel with Pan Am -- a carrier he founded in 1927 to transport mail between Key West, FL, and Havana, Cuba; and Pitcairn Aviation, yet another Curtiss subsidiary that got its start transporting mail, would become Eastern Air Transport, predecessor of Eastern Airlines. Because of this act, Henry Ford's airline was the first airline to transport US mail. Many of these companies who flew the mail started carrying passengers on flights. In 1926, airlines in the US carried 6,000 passengers. By 1930, passengers flying on US airlines had soared to 400,000.

|

The Morrow Board

The same year Congress passed the Contract Mail Act, President Calvin Coolidge appointed a board to recommend a national aviation policy (a much-sought-after goal of Herbert Hoover, who was Secretary of Commerce at the time). Dwight Morrow, a senior partner in J.P. Morgan's bank, and later the father-in-law of Charles Lindbergh, was named chairman. The board heard testimony from 99 people, and on Nov. 30, 1925 submitted its report to President Coolidge. It was wide-ranging, but its key recommendation was that the government should set standards for civil aviation and that the standards should be set outside of the military.

The 1926 Air Commerce Act

Congress adopted the recommendations of the Morrow Board almost to the letter in the Air Commerce Act of 1926. The legislation authorized the Secretary of Commerce to designate air routes, to develop air navigation systems, to license pilots and aircraft, and to investigate accidents. In effect, the act brought the government back into commercial aviation, this time as regulator of the private airlines spawned by the Kelly Act of the previous year. The Bureau of Air Commerce was set up to enforce these regulations. Congress also adopted the board's recommendation for airmail contracts by amending the Kelly Act to change the method of compensation for airmail services. Instead of paying carriers a percentage of the postage paid, the government would pay them according to the weight of the mail. This simplified payments, and it proved highly advantageous to the carriers, which collected $48 million from the government for the carriage of mail between 1926 and 1931.

Ford's Tin Goose

|

The Watres Act and the Spoils Conference

|

Immediately after Congress approved the act, Brown held a series of meetings in Washington to discuss the new contracts. The meetings were later dubbed the "spoils conference" because Brown gave them little publicity and directly invited only a handful of people from the larger airlines. He designated three transcontinental mail routes and made it clear that he wanted only one company operating each service rather than a number of small airlines handing the mail off to one another across the United States. Brown got what he wanted -- three large airlines (American, TWA and United) to transport the mail coast-to-coast -- but his actions also brought political trouble that resulted in major changes to the system two years later.

|

Scandal and the Air Mail Act of 1934

Following the Democratic landslide of 1932, some of the smaller airlines began telling news reporters and politicians alike that they had been unfairly denied airmail contracts by Brown. One reporter discovered that a major contract had been awarded to an airline whose bid was three times higher than a rival bid from a smaller airline. Congressional hearings followed, chaired by Sen. Hugo Black of Alabama, and by 1934 the scandal had reached such proportions as to prompt President Franklin Roosevelt to cancel all mail contracts and turn mail deliveries over to the Army. It was here that Lindbergh fell out with President Roosevelt over the cancellation of the Contract Air Mail Routes.

The decision was a mistake. The Army pilots were unfamiliar with the mail routes, and the weather at the time they took over the deliveries (February, 1934) was terrible. There were a number of accidents as the pilots flew practice runs and began carrying the mail, leading to newspaper headlines that forced President Roosevelt to retreat from his plan only a month after he had turned the mail over to the Army.

|

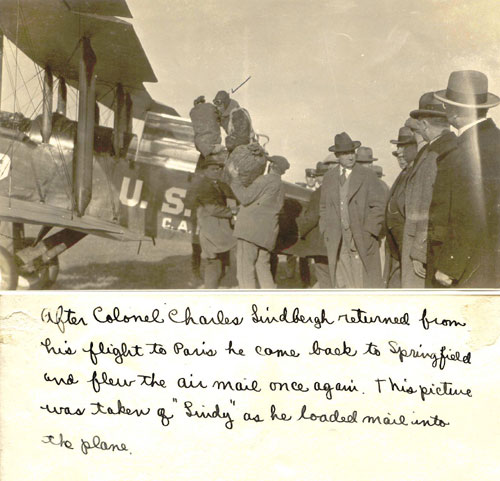

Picture of Charles Lindbergh flying airmail out of Springfield, IL after his famous Paris flight. |

Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | This site is not affiliated with the Lindbergh family,

Lindbergh Foundation, or any other organization or group.

This site owned and operated by the Spirit of St. Louis 2 Project.

Email: webmaster@charleslindbergh.com

® Copyright 2014 CharlesLindbergh.com®, All rights reserved.

Help support this site, order your www.Amazon.com materials through this link.