On May 20-21, 1927, Charles Augustus Lindbergh, a farm boy from Little Falls, Minnesota, beat all the odds and flew alone, non-stop across the perilous north Atlantic to land exactly where he said he would: Paris, France. This achievement commanded the world’s attention because no flyer had been able to navigate 3,600 miles in the air, linking Europe with America.

Just two weeks before Lindbergh’s departure from Roosevelt Field, New York, two French pilots, Nungesser and Coli, left their homeland in a biplane dubbed The White Dove in a bid to fly to America. However, they got lost over the Atlantic and were never heard from again. Their loss was in the hearts and minds of the French people at the very moment of Lindbergh’s dramatic nighttime arrival over the City of Light. The sight of the silver Spirit of St. Louis circling once around the Eiffel Tower sent shock waves of joy throughout the Parisian population, bringing much needed relief from the strain of anxiety over the fate of the missing French pilots.

Lindbergh’s arrival was steeped in a feeling that destiny was at work in the design. As he landed at Le Bourget airfield, 150,000 adoring people rushed the plane and carried Lindbergh above the crowd, passing him hand-to-hand as their collective trophy. He spent the night at the American Embassy, answering questions from the press until well after midnight. His only request, a desire to telephone his mother to assure her of his well-being, captured their interest by putting into perspective the nature of their new hero. He was not a conquering soldier at the phalanx of an invading army, he was just a boy and he wanted to talk to his mother. Moreover, in the morning Lindbergh paid a visit to the mother of pilot Nungesser, encouraging her not to lose hope. This single act of tactfulness endeared him to the French people and immediately elevated Lindbergh to the unofficial status of Ambassador without portfolio. His actions, coupled with his humility, made Lindbergh a superstar. He represented the best of American ideals, and for a generation "he was emulated by thousands of youths as the model of how a man ought to behave. Countless numbers of babies were named in his honor."

As the news of Lindbergh’s actions spread, everyone found something about the courageous young American that they liked. In each country that he visited, he showed respect to the memory of veterans by the laying of wreaths at their monuments. He refused huge commercial offers of cash, asking instead that the money be directed to the families of fallen aviators and he blushed often and deeply at the unaccustomed attention heaped upon him along with the numerous medals, ribbons and keys to cities. Lindbergh’s sense of humor was best illustrated when, after being feted in New York with a snowstorm of a ticker tape parade, he spoke about his receptions in Europe and the building pressure in America for his speedy return. "The Ambassador in London said that it was not an order to go home, but there would be a battleship waiting in a few days," Lindbergh quipped. Taking a cue from this nautical theme, Chief Justice CharlesEvans Hughes said, "We measure heroes as we do ships, by their displacement. Colonel Lindbergh has displaced everything."

West Virginia Connection

Within a few weeks of his return stateside, Lindbergh wrote a 300-page account of his adventure entitled, "We," in reference to his plane, his backers and himself. The book was an instant success, selling more than 635,000 copies. "The royalties paid to the author in the following year amounted to more than a quarter million dollars." Following completion of this book, Lindbergh accepted an invitation by David Guggenheim to embark with The Spirit of St. Louis on a three-month flying tour of all 48 states to promote aviation. Dwight Morrow, a West Virginia native, born at Marshall University and a friend of President Coolidge, persuaded the Guggenheim Foundation to pay Col. Lindbergh $50,000 for the upcoming tour. Morrow later became Ambassador to Mexico and invited Lindbergh to visit him there. It was during a Christmas tour of Mexico in 1927 that Lindbergh met Morrow’s daughter, Anne, whom he married in 1928.

Plans Goodwill Tour

Lindbergh embarked on his tour July twentieth at Mitchell Field, Long Island. Accompanying him in a separate plane piloted by long-time friend Philip Love, age 25, was Major Donald Keyhoe, age 30, from the Commerce Department acting as a personal aide. Communities from coast to coast went into a heightened state of alert in preparation for the arrival of ‘The Lone Eagle.’ Not a day went by without Lindbergh’s name appearing on the front page of newspapers.

West Virginia was slated for a visit and the most populous city, Wheeling, was selected as the site for his appearance. "Civic leaders of the prosperous river city raised several thousand dollars" to purchase all the supplies needed to prepare the West Virginia State Fair Grounds on Wheeling Island for Lindbergh’s address. However, Wheeling had no airport at the time, and since the only federally recognized airfield in West Virginia was located at Moundsville, it was decided that Langin Field, (named for James Joseph Langin, an Air Service hero), would receive the Spirit of St. Louis and welcome "Lindy" to the Mountain State. This airfield was located between W.Va. State Route 2 and the Ohio river, adjacent to the former Alexander Mine. Langin Field was part of a proposed ‘Model Airway,’ an early coast-to-coast flight path. Situated between Washington and Dayton, Langin was often used as a mid-way refueling stop for biplane style aircraft. It had a spacious hanger in which the Spirit of St. Louis was housed overnight. Although nothing remains today of that hanger, a portion of the airfield is kept mowed and the site now is parceled out as a baseball diamond, a large, private vegetable garden and the Moundsville Water Pumping Station. A plaque identifying Lindbergh’s landing was installed in 2003 on nearby W.Va. Route 2.

Local Preparations

All communities along the route from Moundsville to Wheeling purchased bunting, banners and flags to dress the motorcade route in patriotic colors. While Wheeling had a stadium to prepare and a dinner to plan, Moundsville was anticipating a crush of automobile traffic at the airfield and a huge crowd of spectators on Route 2. Local resident, Rev. Dr. Compston, vice president of the Moundsville Aircraft Corporation, privately owned Langin Field. He assured City Council that the grass would be mowed and that the hanger would be appropriately decorated. Moundsville Mayor Jesse Sullivan arranged for a detail of 200 Boy Scouts to be transported from Ohio County to assist the 50 Scouts of Marshall County in securing a cordon at the edge of the airfield to restrain the crowd from pouring onto the field. Council agreed to raise money to purchase lunches for these boys and the Moundsville Chamber of Commerce delivered $200 from members of the business community for this purpose.

In Wheeling, Mayor William Steen prepared a parade route north on Market Street and across the Suspension Bridge to the Fair Grounds. Plans included a speech by Lindbergh to a crowd of 25,000, an address by West Virginia Governor Howard Gore, a lavish banquet for 850 guests at the Scottish Rite Cathedral, with Col. Lindbergh lodging for the night at the Fort Henry Club on 14th Street. Governor Gore traveled by automobile from Charleston, resting overnight at the Warden’s Residence adjacent to the former West Virginia State Penitentiary in Moundsville before continuing his journey to Wheeling. He later took the night train home to Charleston, bolting from the Scottish Cathedral at the last minute in order to secure a berth on a Pullman car.

To improve the visibility for the thousands of spectators viewing the historic landing from the roadway, Moundsville highway personnel cut the vegetation back on the western bank of Route 2 across from the former Tomlinson Homestead, (now the site of a Pizza Hut restaurant). A fully staffed First Aid Station at Langin Field was ‘at the ready’ just in case of an accident, but the expertise of Dr’s. Luikhart, Berman and Nurse Francina McMahon were fortunately not needed.

State police were in position early in the day, but no tickets were given to the first speeder on the scene. At about eleven o’clock, Lt. Jimmy Doolittle of the Army Air Corps at Dayton "suddenly appeared several thousand feet above the Ohio hillside traveling in excess of 120 miles per hour!" His single seat Army pursuit plane approached Langin Field and "suddenly went into a loop. At the peak of the loop Lt. Doolittle straightened out and flew with the wheels of the plane pointed upward." After a time, Doolittle righted the plane and landed it to the cheers of the thrilled spectators. He immediately boarded a car and headed for Wheeling to await Lindy at the grandstand of the State Fair Gounds.

Sighted Over Wheeling

Colonel Lindbergh’s reputation for promptness was as good as his word. At 1:45 p.m. on August 4, 1927 "a small shining monoplane appeared from the north." Downtown Wheeling had swelled to 100,000 as people from three states drew near for the arrival of "NX211," The Spirit of St. Louis. The B&O Railroad ran special excursion cars from as far away as Cambridge, Ohio, Washington, Pennsylvania and Grafton, WV to accommodate the huge crowd. People on rooftops and people lining the streets in Wheeling "went wild for a few moments, cheered and waved," as Lindbergh’s plane came into view. Showers of paper dropped from the roofs and upper stories of every building, draping the storefronts in streamers, ribbons and confetti, "the first time in Wheeling’s history that such a greeting was accorded to a notable."

Lindbergh circled over the business district for five minutes in a descending spiral that brought "We" close enough to the rooftops so that spectators could see "the small side door" and "the glisten and sheen of the whirling propeller blades." As crowds rushed into the streets to get a better view, Lindbergh turned his plane slowly and assumed a southerly heading toward Moundsville, "the city of the airfield." Flying along the course of the Ohio River, the Spirit of St. Louis was seen by people in West Wheeling, South Wheeling, Mozart, Bellaire, Benwood, Shadyside and Glendale.

Lands At Moundsville

At 2:00 p.m. on that hot August afternoon, the small silver bird came slowly into view from the north. As the Spirit of St. Louis approached Glendale, a paddlewheel riverboat on the Ohio River was the first to signal the arrival by sounding its whistle. The airplane circled the city of Moundsville once before lining up for a perfect three-point landing at Langin Field. A sustained cheer went up from 20,000 spectators and their roar was joined by a chorus of steam whistles from the many factories located at Moundsville, whistles that were then "tied down." The crowd surged forward pouring onto the field, but they were kept well back from the plane by a special contingent of state police officers. Meanwhile, Col. Lindbergh took his time securing the Ryan monoplane before climbing to the ground to shake hands with the reception committee.

Eyewitness to History

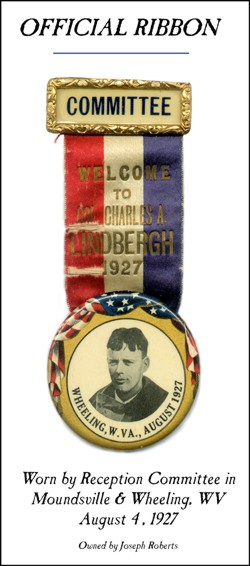

One Moundsville resident, Dr. Robert Durig, was an eyewitness to Lindbergh’s landing. He supplied a photograph of the Spirit of St. Louis taxiing to a stop just moments after touchdown, and also an actual Committee Ribbon worn by one of the welcoming committee dignitaries. As a 12-year old boy, Bob Durig was keenly interested in airplanes. He is an accomplished pilot, and until his retirement was a frequent flyer throughout the tri-state area. He remembers seeing Lindbergh near the B&O railroad tracks in the open touring car that carried Lindy and the welcoming party to Wheeling. It seems that after the motorcade was made ready for their procession to the ‘Friendly City,’ a passing steam train got to the railroad crossing first thus delaying the officials for almost five minutes. Those nearest the railroad crossing had plenty of time to appreciate the handsome countenance of the tousled haired, air hero. Bob Durig was one.

Unfortunate Haste

From the airfield, the party followed Western Ave. to Seventh Street, turning north on Jefferson Avenue. However, perhaps because of the delay caused by the unexpected train, the Wheeling steering committee told the police motorcycle escort to pick up speed through the heavily crowded Jefferson Avenue business district. When the troopers protested that Moundsville people wanted to see Lindbergh, the reply from the Friendly City’s steering committee was, "To [heck] with Moundsville; this is Wheeling!" Thereupon the official car raced through the crowded streets at 40 to 50 miles per hour. People at the Strand Theatre corner say it was "a flash" across Fifth. At First Street, the car outpaced the police motorcycle escort and the reckless pace did not abate through Glendale, sending clouds of dust on the crowds lining the curbs.

Whirlwind of Activities

Once the official car reached the city limits of Wheeling it slowed down to a snails pace and 100,000 happy faces smiled out at the aviator. Just after three o’clock on that August afternoon, Lindbergh was escorted to the grandstand at the West Virginia Fair Grounds on Wheeling Island. There he was introduced to WV Governor Gore, Otto Schenk, Mayor Steen and other dignitaries. In a laconic style characteristic of Lindbergh’s manner of speaking, he got straight to the point about the importance of building new airports to advance the cause of commercial aviation. He complimented Langin Field, but said that a more centrally located field would be better for Wheeling. He spoke for less than three minutes before abruptly finishing with his signature, "I thank you." The crowd, trained by local politicians to expect interminably long speeches, was caught completely off guard. Before their surprise subsided, Lindbergh and Gov. Howard Gore quietly disappeared beneath the grandstand to the safety of a closed automobile and were quickly motored away.

Lays Wreath At Linsly

Following Lindbergh’s appearance on Wheeling Island, he was driven to the campus of Linsly Institute where he laid a wreath at the foot of the Louis Bennett memorial statue, "The Aviator." It was a simple ceremony attended by a detail of 20 cadets, Dean Guy Holden, Otto Schenk, Harry Wilson, E. B. Hopkins, Lieut. James Doolittle, Lee C. Paull, Jr., Carl Schmidt, T. H. Pollock, E. W. Stifel, and Donald Keyhoe. The Louis Bennett Memorial is a bronze statue of a World War I Air Service Pilot standing erect, his eyes focused skyward, wearing a pair of sensitively carved avian wings after the manner of a guardian angel. Augustus Lukeman, creator of the colossal Confederate Memorial at Stone Mountain, Georgia, carved the awe-inspiring statue at the behest of Sallie Maxwell Bennett, as a lasting tribute to her son. Louis Bennett, Yale 1917, was a pioneer aviator in the Wheeling area who formed the West Virginia Flying Corps in Beech Bottom with the aim of training aerial cadets for military service. He had a distinguished flying career with the RAF and was West Virginias only ‘Air Ace’ during WWI.

Returning to the Fort Henry Club, Lindbergh had very little time to relax. He dressed for a banquet held in his honor at the Scottish Rite Cathedral. At the dinner he spoke again about the need to develop the air transportation industry, and at 9:00 p.m. the 850 guests bade him retire for the night to rest for his flight to Dayton the following day.

Commends Langin Field

He was expected to depart Langin Field around noon the following day, August 5, 1927, but got a jump on the crowds by arriving early in the crisp, morning air at 10 o’clock. The first order of business was a thorough inspection of the Spirit. Once this was done he spoke with Dr. Compston about Langin Field. "It’s a fine field," said the air hero. "I never landed on any field where conditions were so clear and clean as at Moundsville." Lindbergh then took some time to inspect a new airplane, the first produced by the fledgling Moundsville Aircraft Corp., a biplane with a Chevrolet engine. Accompanied by his aides and friends, Donald Keyhoe, Charles Kinkaid, Philip Love and Jimmy Doolittle, Lindy "inspected the small ship minutely. He climbed under it, inspected the fuselage, looked over the controls and instrument board, felt the wings and tested their strength." Commenting on the prototype biplane, he said, "The ‘Lone Eagle’ appears to be a fine little plane and I wish the Moundsville Airplane Corporation success." The tiny plane was dedicated "The Lone Eagle" by James Doolittle, who christened it in Lindbergh’s honor by smashing a bottle of water over the nose. The name is appropriate, said Doolittle, "For as Lindbergh was alone in this great achievement, so this plane is alone in a new field of commercial airplane construction." (Note: the Moundsville Airplane Corp. was originally located on Tenth Street in the building now occupied by the Boso and Son Towing).

Waves To Crowd

With all amenities now at a close, the famous Charles Augustus Lindbergh signaled goodbye to the "thousand or so persons who chanced to be at Langin Field at the time." Escorted by six state troopers to his beloved Spirit of St. Louis, he smiled as he donned his flight coat and leather helmet, waving to the crowd before climbing into the cabin. "We" departed at 10:30 and circled over the city for ten minutes before heading north towards Wheeling. A few minutes later another Ryan monoplane bearing Love, Keyhoe and Kinkaid took off in pursuit.

This quote, by Craig Shaw, former Editor of The Moundsville Daily Echo newspaper appeared in the August 5th edition:

"Crowds continued to flock to Langin Field until late in the afternoon, unaware that Lindy had gone. The picturesque youth who has stirred the imagination of millions endeared himself in the hearts of all who saw him at Langin Field or along the line of the parade. His simple unassuming manner, has stamped him as an American of the finest type and one whose memory can never be eradicated."

Materials for this story derived from primary sources and eyewitness accounts. Newspapers researched include: Wheeling Register, Wheeling Daily News, The Telegraph, Moundsville Daily Echo, Moundsville Journal, Wheeling Intelligencer, Washington [PA] Reporter, Bellaire Leader. Dates of search: July 1 through August 31, 1927.

This story appeared in the Moundsville Daily Echo, August 1, 2002, and the Sunday News Register, Wheeling, WV, August 4, 2002 and the West Virginia Historical Society magazine, Volume XVIII, No. 3, July, 2004.

Reprinted with permission of Thomas O. James, toj33@hotmail.com, © 2002